A Brief Look at Nipmuc History

The people the English referred to as Nipmuc, or “fresh water people” occupied the interior portion of what is now Massachusetts and parts of Rhode Island and Connecticut. The present-day boundaries of the original homelands included all of central Massachusetts from the New Hampshire/Vermont borders and south of the Merrimac Valley southerly to include Tolland and Windham counties in Connecticut and the NW portion of Rhode Island. To the east, the homelands included the Natick/Sudbury area going west to include the Connecticut River Valley.

The people lived in scattered villages throughout the area including Wabaquasset, Quinnebaug, Quaboag, Pocumtuc, Agawam, Squawkeag, and Wachusett. Their economic and subsistence cycles consisted of hunting, gathering, planting, and harvesting in their seasons. These villages were linked together by kinship ties, trade alliances, and common enemies. They lived in wetus, which could be moved to other encampments. Often thought of as wanderers, they were instead careful planners and good stewards of the land upon which they lived.

There are scattered references throughout history to Europeans landing on the coasts of Canada, Maine and the islands nearby. In 1497, John Cabot landed on New Foundland establishing new fishing grounds for Northern Europeans. The French attempted several times to colonize the Canadian and Maine coastlines in order to capitalize on the fur trade. Deadly epidemics resulting from these encounters ravaged the Native population. Current scholars estimate a possible 80% mortality rate. Later, when the English began to settle the area, they took the vacant villages and abandoned cornfields as a sign from God that they were meant to supplant the Indians as the rightful inhabitants of the land.

(Ojibway oral history tells that a sign was given and the people knew that a terrible thing was on its way to destroy the people. Therefore, they left and traveled west to new lands taking the sacred fire with them until it was safe to return it to the homelands. They refer to the Indians in New England as the ones that stayed behind.)

The earliest known contact between Nipmucs and the English was possibly in 1621 at Sterling, MA where Nashawanon was sachem. The Nipmucs initially had friendly relationships with the Europeans. In one instance, a Wabaquasset native, Acquittimaug, walked from his home to Boston carrying corn for the starving colonists. It is estimated that there were 5,000 to 6,000 Nipmucs when the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth in 1620. The bulk of the Nipmuc population lived along the rivers and streams connected to the Blackstone, Quaboag, Nashua and Quinebaug.

In the 1640’s, the Rev. John Eliot of Roxbury began preaching to the Natives of Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut. Between 1650 and 1675, he worked to establish “praying plantations” or villages to aid in the conversion of the Indian population. He felt that by removing them from their tribal villages and creating towns for them the natives would eventually forsake their “ungodly” ways and emulate the English. In the towns, the Native people were forbidden to practice their traditional ways, wore English style clothes, lived in English style homes and attended the Puritan church. Eliot himself set up seven of the towns, known as the old praying villages, Wamesit, Nashobah, Okkokonimasit, Hassanamesit, Makunkokoag, Natick, and Punkapoag. Nipmucs and other natives who joined these towns did so for a variety of reasons. Protection from Mohawk attacks, curiosity about English ways, economic survival, education, and the availability of food and clothing were some of the factors involved in Native people voluntarily moving to the towns. Natick was the first town and church to be established and Natives were trained there to serve in the other Indian churches. Word spread and Nipmucs further west set up seven more praying villages, known as the new praying towns. These included Manchaug, Chabanakongkomun, Maanexit, Quantisset, Wabquisset, Packachoog, and Waeuntug.

Further encroachments by the English upon Indian land increased hostilities between the Natives and the English colonists. Some of the praying Indians forewarned the English of impending war with the Wampanoag leader, Philip, son of the Massasoit. In April of 1675, John Sassamon, a Wampanoag who was an informer for the English, was found murdered. Two other Wampanoags were found guilty by the English and executed. The English blamed Philip for the murdered man and accused him of planning war against the English. Philip escaped arrest by fleeing to Pocasset where the village of his sister-in-law, Weetomoe was located. Philip sought help from the Narragansetts but was refused. He then went into Nipmuc country where many were anxious to follow him into battle. War had begun and some of the praying Indians chose to fight and others to scout for the English. In July of 1675, the Mohegan traveled to Boston and pledged their support for the English.

English colonists began voicing their fears of Indian attacks. They believed that the praying Indians would join the war on the side of Philip. In August of 1675, the colonial government made a decision to confine all Indians to one of five plantations – Natick, Nashobah, Punkapog, Wamesit, and Hassanamesit. Any Indians found outside of these limits are subject to jail or death. This severely limited the Natives’ way of life. They could no longer hunt, harvest, or trade.

The murmuring against the praying Indians continued and on October 30, 1675, the colonists forcibly removed the residents of Natick to Deer Island in Boston Harbor. By the end of the year, they were joined by the Punkapoag and the Nashobah. The Hassanamisco Indians were attacked and carried off by the Nipmuc fighting for freedom in November of 1675. That same month, the English fired upon Wamesit, killing innocent women and children. The Wamesits, besieged by both the English and Nipmuc neighbors asked the colonial government for protection and were sent to Deer Island as well. Before the end of the war, even the praying Indians that spied and fought on the English side were sent to Long Island in Boston Harbor as prisoners of the war.

Philip was eventually killed and the war ended, nearly a year later. The praying Indians were released from the islands and allowed to inhabit only certain Indian towns, Natick, Dudley (Chabanakongkom), Hassanamesit, and Wabaquasset. The Nipmucs who had resisted the English invasion were killed, sold into slavery or went into hiding, often with tribes to the north and west of Nipmuc country.

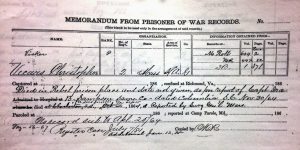

The English pushed further into Nipmuc country determined to make permanent settlements in the area. To survive, many Nipmucs moved from the reservations and adopted English habits and dress. They still practiced seasonal mobility and itinerant trading, selling baskets, brooms, and herbs to the white settlers. Nipmuc men fought in Queen Anne’s and King George’s Wars in the 1700’s and participated in the Abenaki resistance in the 1720’s, but they fought against the Abenaki. Nipmuc men also served in the Revolutionary War on the American side. During the Civil War, Nipmucs served in both the 54th and the 55th regiments of the Massachusetts army.

Increasing numbers of Nipmucs moved into the growing towns in search of work and mates. Serving in the wars caused a shortage of Nipmuc men, therefore Nipmuc women began to marry non-Natives, especially African-Americans in order to have children, continue the tribe and for economic survival. Intermarriage between Nipmuc people continued as well. Records from the 18th and 19th centuries show multiple marriages between Nipmucs from Dudley, Natick, Woodstock (Wabaquasset), and Grafton (Hassanamisco). Although they lived further apart, Nipmucs continued to maintain kinship ties, receive annuity payments from the state, and established Nipmuc enclaves away from the traditional reservations. Nipmucs, like other Indians in MA, were considered wards of the state. Indian commissioners and guardians were appointed over them to manage their lands and debts. Many of these guardians stole from the Nipmucs by illegally selling land to pay their own debts. In 1849 and 1859, the Commonwealth commissioned a count of Indians and a report on their condition. These reports, the Bird/Briggs Report in 1849 and the 1859 Earl Report, are used to this day as evidence of continued interactions between Indians and Massachusetts.

In June of 1869, “Indians and people of color, heretofore known and called Indians” became citizens of Massachusetts through the MA Indian Enfranchisement Act. The MA legislature tried to follow Federal Reconstruction-era race policy and came to the conclusion that since there were few “pure-blooded” Indians left and since the state had always been committed to freedom for the African-American, why not the Indian? Unfortunately, the act threw open for sale Indian lands to non-Indians. Lands held in common were divided up as in the case of Dudley.

In 1871, the last of the Dudley land was sold and five of the families were placed in a tenement house on Lake Street in Webster. The rest scattered, moving with other Nipmuc families living in Woodstock, Worcester, Providence, and Hassanamisco. Worcester developed strong Indian enclaves in mainly African-American neighborhoods. Nipmuc activities became centered on the Hassanamisco Reservation. Events such as the Annual Clambake and elections on the 4th of July were times for Nipmucs to gather and discuss tribal business. In 1886, living members and descendants of the Pegan Band of Nipmucs (the Dudley Indians) each received $61.61 as their share of the proceeds from the sale of the Dudley reservation.

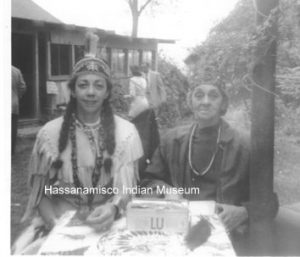

In the early 1920’s, a variety of Pan-Indian movements including the Indian Council of New England and the National Algonquin Indian Council created increased opportunities for Nipmucs to practice and share traditional ways and to become politically involved in Indian issues. The Cisco family at Hassanamisco became tribal leaders and formed the Mohawk Club which met in Worcester to discuss and plan educational, cultural and social events. The name was later changed to the Hassanamisco Club with meetings held at both the reservation and in members’ homes in Worcester. Tribal leaders during this time included Sarah M. Cisco, James Lemuel Cisco, and Althea Hazard.

Annual clambakes and elections continued in the late 30’s with Sarah Cisco remaining in the leadership position. In 1937 and 1941, she petitioned the Massachusetts Legislature for pensions for Hassanamisco people and for the upkeep of the reservation. In 1938, she also filed a claim for the return of Lake Ripple, a man-made lake in Grafton, to the Hassanamisco people. During World War II, things were quiet in Nipmuc country. Nipmuc men went to war and the women worked in factories and raised children. After the war, community gatherings resumed. Some of the events at Hassanamisco became open to the public but meetings where tribal issues were discussed remained open to Nipmuc people only. Election Day continued with tribal members spending the entire weekend camped out on the reservation. Requests for assistance were made to the Indian Claims Commission and the North American Indian League of Nations.

The Nipmuc Indian Chapter of Worcester formed in the 1950’s amid disputes between Worcester Nipmucs and the Hassanamisco leadership. Among those active in the Nipmuc Indian Chapter of Worcester were William and Elizabeth Moffitt, Lillian Brooks King, Roswell Hazard, Mabel Hamilton, Jessie Mays, and George Wilson. The chapter was formed to provide for the educational and cultural advancement of Nipmuc people with the hope of beginning other chapters in other cities. The split was soon mended though and tribal gatherings continued at Hassanamisco. The Annual Hassanamisco Fair continued in July, Massachusetts Indian Day was celebrated in August, and the Hassanamisco Council met regularly. In 1962, the Hassanamisco Foundation was created to ensure that the reservation would be preserved intact and that other provisions were made for the Cisco family line. Zara Cisco Brough became tribal sachem and assumed leadership responsibilities. Zara was actively involved in Grafton town politics and successfully won dredging rights to Lake Ripple for Hassanamisco. As sachem, she worked for the protection of tribal rights and the preservation of the reservation.

In 1974, the Massachusetts Commission on Indian Affairs was created and in 1976, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts officially recognized the Hassanamisco Band of Nipmucs. Nipmucs from other family lines became more active on the Hassanamisco Council. Members of the Council of Chiefs included Walter Vickers, Joseph Vickers, Charlie Hamilton, George Cisco, Peter Silva, Sr., and Samuel Cisco. The Hassanamisco Foundation was amended to ensure that if the Cisco line ended the reservation would never leave Nipmuc hands. Zara made plans for “New Town”, a 500-acre town on what is now Grafton. She petitioned the Governor and the legislature for the state-owned land to create this Indian town but the land was eventually given to Tufts University for a veterinary school.

The Chaubunagungamaug Band, under the leadership of Edwin Morse, formed in 1981 to revitalize the Dudley Band of Nipmucs. Land was donated to the Chaubunagungamaug for a reservation in Thompson on the original Dudley reservation. Walter Vickers was named head chief by the sachem, Zara, and the Hassanamisco Council in 1982. Later that year, he conducted the ceremony to install Edwin Morse as chief of the Chaubunagungamaug band. The Reno Report, researched and created by Zara and Dr. Stephen Reno, became the official petition for recognition in 1984.

The nineties brought much activity, both good and bad. The Nipmuc Tribal Acknowledgment Project, begun 1989, continued the important research for federal recognition and compiled a census of the tribe. In 1995, the Hassanamisco and the Chaubunagungamaug bands came together to work towards recognition thus uniting tribal members under one banner, the Nipmuc Nation. Unfortunately, the unification did not last long. In 1997, the Chaubunagungamaug band split off from the Nipmuc Nation to attempt federal recognition on its own. The split was due to diverse factors including the division of power and tribal roll guidelines. Several Nipmuc organizations were founded during the nineties. The Nipmuc Indian Association of Connecticut was founded by Joan Luster to provide educational, cultural and traditional services to CT Nipmucs. Cheryl Stedler began publishing the Nipmucspokhe newsletter in 1994 to keep tribal members everywhere informed. In 1997, the Nipmuc Women’s Health Coalition, headed by Liz Coldwind Santana-Kiser, was formed to educate and inform Nipmuc women and their families about health prevention, healthy practices, and traditional healing. To assist the tribe in economic and community development, the Nipmuc Indian Development Corporation was created in 1999 by a group of concerned Nipmuc people.

Despite the hardship and multiple setbacks, the Nipmuc Nation – Hassanamisco band in January of 2001 received a positive preliminary finding on federal acknowledgment. The positive finding was quickly reversed by the Bush Administration. After many years of appeals, the Nipmuc Nation lost their battle for federal recognition. In 2022, the Hassanamisco Band left the confines of the Nipmuc Nation and continues to steward the reservation and promote the continued existence of Nipmuc people.

– CTH